Attempting to write a screenplay is a new and confusing endeavor for many writers. If you are starting your first screenplay there are a lot of places you can go wrong. This article is a guide to the fundamentals of screenplay writing. It covers appropriate styles and formats. If you are already familiar with the basics of screenplay writing, this article will not likely offer any new information. For more advanced screenwriting information see my article Screenwriting: A Not-So-Basic How-To (coming soon).

The first thing to know when writing a screenplay is that the formatting rules of screenwriting are strict and unflinching. Attempting to make your screenplay look unique or stand out will only make it look unprofessional. I am not personally a fan of structure and rules, especially in writing. But when it comes to screenwriting you must follow the rules if you wish to be successful.

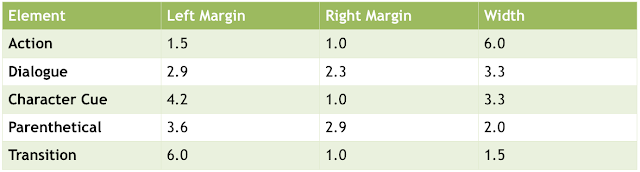

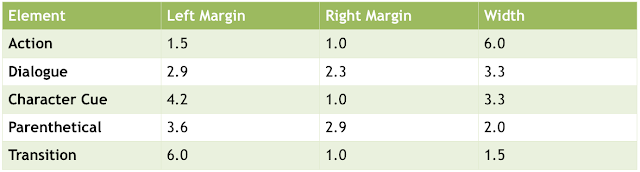

The first of these rules has to do with formatting. Screenplays are almost always written in 12-pont Courier font. Unfortunately, if your screenplay is not written in this font it will likely end up in the trash bin of whoever you send it to without ever being read. That is simply the way the film industry works. Don’t follow the rules and you won’t be taken seriously. The page should be laid out according to this table:

|

This table is based on information from storysense.com which is a good place to look if you have any more questions after finishing this article.

|

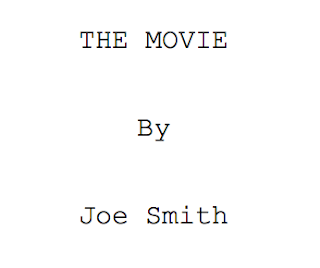

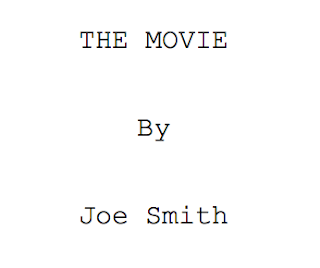

Any screenplay* should begin with a title page laid out like this:

|

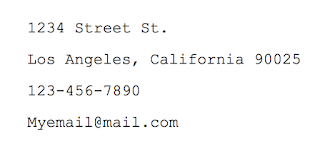

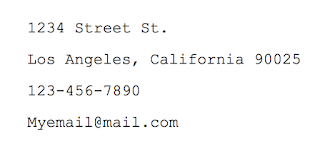

The title and author should be on line 25 and centered horizontally. There should also be four blank lines between the title and the “written by” line. There should also be a single blank line between the “written by” line and the actual name of the screenwriter. It is also a good idea to include your contact information on the title page. If you decide to do this it should be done in the bottom left corner of the page. The last line of the contact information should be one inch from the bottom of the page. Contact information should include a full mailing address followed by a phone number and/or email in this format:

Include page number four lines down from the top of each page, aligned with the right margin. Only use the number. Do not preface it by the word “page” or “pg.” Place a period after the page number. The page count should not include the title or “fly” page. The count should begin with the first page of the actual script. However, standard formatting dictates that the first page not have a page number actually on it. The second page should be the first with a page number on it beginning with “2.”

There should be two spaces following any punctuation. Lines should be single spaced (unless writing television scripts). Page breaks must occur only after a sentence. Never page break mid-sentence. This applies to dialogue as well as description.

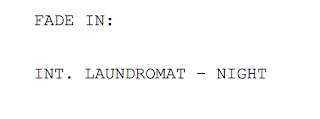

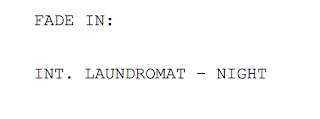

It is important to know that the essential prose style of screenplays differ greatly from fiction prose. There are a few dos and don’ts you should know before beginning your screenplay. First and foremost is that a great deal goes unsaid in a screenplay. Much has to left to the director and the actors to create. This can be difficult for fiction writers who are used to having full creative control over their writing. Scene Headings describing setting should be clinical and simple. Don’t go into detail about the room a person is in. Only include the essential details. What is the setting? A doctor’s office? An abandoned mine? Someone’s apartment? A good rule to stick to is that no setting description should be longer than five words. There are obviously exceptions but in general this is a good way to gage if your scene heading is too long. Following an introduction such as “FADE IN” the setting should also always be the first thing described. Even if a scene begins with a close up, it is important to let the director and cast know exactly where they are. Remember that as a screenwriter you are no longer writing for a reader. Your writing is not a finished product and will never be seen as-is by the intended audience. Even after you have finished all your edits and rewrites, your screenplay will still be under construction. It’s OK to let the parts show a bit. In general, a setting description should look something like this:

Notice that the first line is a transition. “FADE IN” describes fading into the scene from a black screen. I will talk more about transitions and shot descriptions in a moment. For now, look at the nest line. This is the first setting and there should be a single blank line between it and the “FADE IN” line. “INT.” stands for interior, letting you know that the scene takes place inside (as opposed to EXT. for exterior). Never spell out “interior” or “exterior” completely. Always use the standard short hand. If a scene moves from an interior to an exterior setting (or vice versa) the correct formatting is as follows: “INT/EXT.” or “EXT/INT.”

Look at the setting itself. Notice how simple the scene setting is. “LAUNDROMAT - NIGHT” is all the information that is given. In some cases it may be necessary to include a time in the setting such as “LAUNDROMAT (1973) – NIGHT” The rest is up to the director. More details can be included if necessary as the scene unfolds.

When writing dialogue, place the character cues 4.2 inches from the left margin and the actual dialogue 2.9 inches from the left. Keep character cues short and simple. Prominent characters generally go by their first name. If you need to break a page in the middle of dialogue do so in-between sentences and include the word “(MORE)” on its own line in all caps and parenthesis. Avoid using symbols or numerals in dialogue. Spell numbers out. Never use italics or all caps in dialogue. Underscore for emphasis. If two characters are speaking simultaneously use multiple columns. In this case it is acceptable to vary the margins on speech columns.

When moving between scenes there are a few common types of transition you can use. Most of them are superfluous. Transitions such as “SMASH CUT” and “QUICK CUT” are unnecessary. For the most part, you should stick to using “FADE IN,” “FADE OUT,” “DISSOLVE TO,” and “CUT TO.” You should only use the “FADE IN” transition once, at the very beginning of the script. Likewise, “FADE OUT” should only be used at the very end of the script. The rest of the time use “FADE TO” to describe a FADE OUT and a FADE IN back to back. The finally FADE OUT should be left aligned rather than right aligned. It should be followed by the line: “THE END” in all caps, underscored, and centered on its own line.

Descriptions such as “PAN TO,” “DOLLY IN,” or “CRANE UP” should be used as little as possible. Only include shot descriptions which are absolutely necessary to the story. The more shot descriptions you use, the more you usurp the job of the director. This is generally seen as inappropriate in screenwriting.

When describing action use simple, clear language. Avoid the sort of wordy and descriptive language you may be used to as a fiction writer. Generally, a scene should look something like this:

|

In terms of length, most modern scripts are 100-120 pages. Generally, each page is representative of about one minute in actual runtime. Do not print the script double-sided.

Screenwriting is far more complicated than most other forms of writing. Though the prose itself is, in a way, simpler., it can take a while to get the hang of the many formatting rules. There is a seemingly endless list of these rules and the ones I have described here are only the most fundamental. For more advanced information on screenwriting see Screenwriting: A Not-So-Basic How-To (coming soon), which covers more complicated topics including Slug Lines, Parenthetical Direction, Flashbacks, Montage/ Series of Shots, and more detailed information about scene headings.

For now, good luck and good writing. Be brave, be sincere, and have fun!

*margins on examples may not conform to specifications exactly. For exact margins refer to the margins table and not examples.

No comments:

Post a Comment